High Speed 2 (HS2), the planned new rail route from London to the cities of the Midlands and the North, is a controversial project, about which I have been rather agnostic. What are the pros and cons?

Demand for rail travel has been growing rapidly, with passenger numbers doubling over the past 20 years since the industry was privatised. Has this growth arisen because of or despite privatisation? Probably both: the train operating companies have invested in new rolling stock, which attracts customers; but growth has also been the result of road congestion, digital technologies allowing productive work on rail journeys, the shift of the economy from manufacturing to business services located in city centres, and more people living in cities without a car.

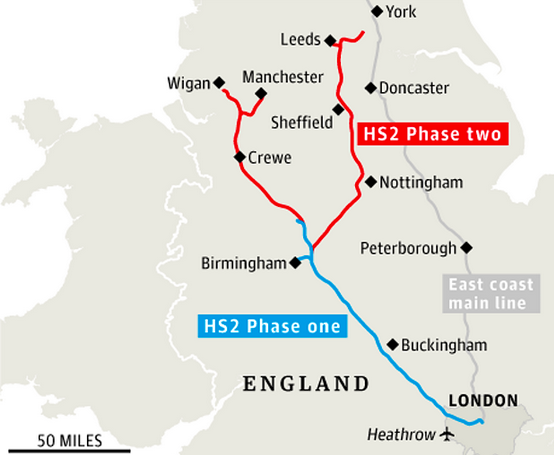

We can expect demand for rail travel in Britain to continue to grow, driven both by population increase and by the attractions of an improving network that offers fast and reliable travel. Hence the need to invest in track, stations, signalling and rolling stock. Additional capacity on existing routes is publicly acceptable despite weekend interruptions to services, and can be cost-effective if spare capacity exists, although the decade-long modernisation of the West Coast Main Line in recent years was problematic, involving delays and cost over-runs. Longer trains and longer platforms, with a smaller proportion of first class seats, is one approach. Most rail investment involves improving existing routes, or occasionally reviving disused track, for mixed passenger and freight use. The main exception is HS2, a new build high speed route for fast passenger trains only.

The development of HS2 is being carried forward by a Government-owned company. A Bill is currently being considered in Parliament to secure powers to construct and maintain the first phase, London to Birmingham. The strategic case for HS2, published in 2013, argues that this offers a step change in north-south connectivity, at a cost for a high speed line of 9% more than a conventional railway. Travel time from London to Birmingham, for example, would be reduced from 1hr 21min to 49min. Long distance trips transferred to the new line will free up capacity on existing services for additional commuter services.

Economic case

An important part of the case for HS2 is the economic case. On the standard approach to transport cost-benefit analysis, where the main economic benefit is time saving through faster travel (valued because this permits more productive work or desired leisure), the benefit:cost ratio for the first phase is estimated to be 1.7 and for the whole route 2.3. These values take some account of a debate about the value of time savings when one can work on the train.

The Economic Affairs Committee of the House of Lords has issued an illuminating report critical of the case for HS2, making the following key points:

• Business travellers, who derive 70% of the transport benefits, should pay higher fares than for standard rail journeys.

• Long term growth of demand for rail travel is unclear; overcrowding arises from commuters, not long distance users who would most benefit from high speeds.

• The economic impact is unclear; the economic case based on the value of time saving is unconvincing; and London may be the biggest beneficiary.

• There are better ways of spending £50bn, the cost of constructing HS2, track and trains.

The Government responded to the House of Lords report, rebutting the criticisms without shedding further light on the economic case.

Assessment

The economic case for HS2 relies largely on estimates of the benefits to business travellers from speedier journeys, for instance saving half an hour between London and Birmingham. The value of this benefit depends on the future number of travellers and on estimates of the value of time savings – both subject to considerable uncertainty. The Department for Transport has recently published research findings that would increase the value of time savings from long distance rail travel.

What the conventional economic case does not illuminate are the benefits to the cities of the Midlands and the North of the new rail route arising from new urban developments. To include the enhanced value of land and property that would arise from improved access and connectivity would be double counting the time savings benefits, according to the orthodox view. This view has nothing to say about distribution of benefits other than to different classes of travellers (business, commuters, leisure) – nothing about spatial distribution as between cities and regions, nor about benefits to existing land and property owners.

An approach to economic analysis of transport investments that was based on spatial economics would allow changes in land use and enhancement of land and property values to be taken into account as reflections of the economic benefits of improved access. This is what happens, in effect, when a particular transport investment is promoted as part of a more general development – an example is the planned extension of the Northern Line tube in London to allow the development of the Nine Elms riverside site.

Appraising the development potential in the cities to the north of London that would result from HS2 is difficult, given the many uncertainties. Much depends on the efforts made by the city authorities to take advantage of the new rail route, efforts that are seemingly being undertaken with some enthusiasm, as well as on the commercial judgement of the developers. But it is clear that the range of uncertainty associated with such a large, single, hopefully transformational investment is substantial. So unless the benefit-to-cost ratio is large (unlikely for HS2 however valued), the political judgement to proceed could not be based on a clear economic case.

We cannot be sure that the main beneficiaries of HS2 will not be businesses based in London. The challenge for the cities to the north is to prevent this outcome.