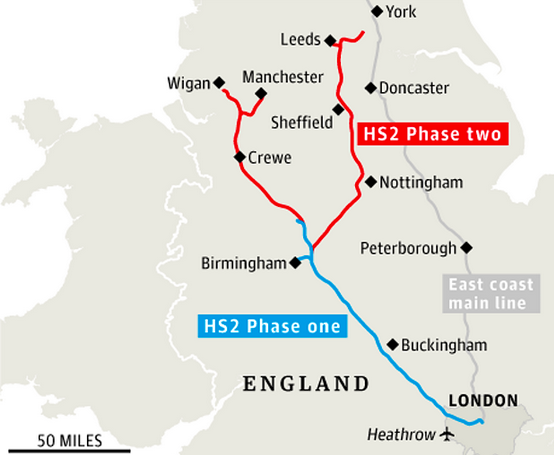

The Prime Minister’s recent announcement that the HS2 rail line will not now continue from Birmingham to Manchester and beyond raises issues both immediate and long term. Immediately, there is the question of how that money saved is to be reallocated. In the longer term, the question is whether we have an analytical framework that is both sufficiently complete and robust to be relevant to major projects whose gestation and implementation may span decades.

The Prime Minister’s principal stated reasons for scraping the lines beyond Birmingham were cost escalation, delays to construction, and the impact of Covid on travel behaviour. The money saved would be devoted to improved transport schemes outside London, mainly in the Midlands and the North of England, he argued. He also pointed to the huge chunk of the national transport investment budget taken up by HS2, for which Rishi Sunak implied was a relatively narrow user base and geography.

Certainly, the cost estimates of HS2 have grown substantially since the scheme was first announced in 2010. The initial cost of the full Y network, comprising both the first section to Birmingham and legs to Manchester and to Leeds, was put at £37 billion (2009 prices), but by the time of publication of the Full Business Case in 2020, this had risen to £109 billion (2015 prices), with further cost escalation in prospect due to inflation and real cost increases as earlier optimism bias is exposed.

The economic benefits projected in the Full Business Case were largely to rail users, predominantly £39 billion (present value, 2015 prices) as a result of reduction of train journey times. There were also significant benefits from reduction in crowding on the conventional network, as well as reduction in waiting and greater reliability as the network was enlarged by adding the new line, which, together with some smaller benefits, yielded net transport user benefits of £74 billion. To this was added benefits from agglomeration and other wider impacts to reach £94 billion net benefits. Taking into account revenues from fares resulted in a benefit-cost ratio (BCR) declared in 2020 to be 1.5, categorised as low-to-medium value for money.

Clearly, any further cost escalation since 2020 was potentially likely to tip the BCR into low value territory, a most unwelcome position for the largest single UK transport infrastructure project ever. But do the estimates of benefits reflect the reality? We need to go back to the core proposition, endorsed by the main political parties.

The stated intention of HS2 was to reshape the national economy by joining up the North, Midlands and London, effectively halving the journey times between the centres of the UK’s largest cities. This, it was contended, would allow businesses to invest beyond London whilst still retaining ready access to it. It was argued that the scheme would contribute towards sustainable growth in towns, cities and regions across the country, spreading prosperity and opportunity more evenly, acting as a catalyst for job creation, the development of new homes and ultimately, the regeneration of major cities and towns along the route.

This thinking was more heroic than business-like. The assumption of conventional economic investment appraisal is that the transport user benefits provide a good estimate of the ultimate benefits that arise as perfect markets redistribute benefits amongst the various beneficiaries, including land and property owners who gain from the improved access, the businesses that occupy the new premises, and people who occupy new homes. This itself is an unrealistic assumption in general. Moreover, in the case of HS2, for which the distribution of benefits between London and the cities of the Midlands and the North is crucial, estimation of spatial distribution was not attempted in the economic appraisal of the investment – and indeed is a difficult matter to predict.

Consider, for instance, a business with headquarters in London and a branch office in Birmingham. It might take advantage of the faster rail connection offered by HS2 to close the branch office, serving clients in Birmingham from London; or it might expand the Birmingham branch where office rents and housing costs are lower, on the basis that staff could get up to the head office speedily as necessary; or arrangements may be left unchanged, staff benefiting from the faster business travel spending more time in the office; and, of course, the increase in working from home as a result of the pandemic must influence all the possible business decisions. What might emerge could be an instance of what is known as the Two-way Road Effect, whereby improved accessibility between two regions may benefit prosperous areas rather than the poor areas targeted by the scheme, sucking activity away rather than bringing it in.

Given that the intention of HS2 has been to boost the economies of cities and region to the north of London, uncertainty about distribution of economic benefits means that the value of the investment was always hard to judge. Much would depend on the ability of the connected cities to take advantage of the new rail route to put in place city-centre development around new stations plus local transport infrastructure to speed travellers to and from their final destinations beyond the rail terminal. These longer origin to destination considerations can change to value of the high speed rail journey itself. The HS2 Full Business Case included an annex outlining hoped for developments around the new Curzon Street station in Birmingham, which illustrated the economic possibilities. But these did not constitute part of the economic case for the investment, to avoid double counting travel time benefits. This illustrates how notional time savings are tenaciously preferred to estimates of real-world benefits when applying the orthodox methodology to the appraisal of transport investments.

The inadequacy of the economic analysis, likely involving underestimation of the benefits from development, may well have contributed to the truncation of the HS2 project, given the latest BCR estimate of 0.8-1.2 quoted by the DfT.

A comparison with Crossrail

Another major rail investment that ran over time and budget was London’s Crossrail, renamed the Elizabeth Line on opening. Fortunately, those responsible kept their nerve. The project was not skimped or cancelled and has proved to be a great success, an example of a modern metro whose performance and popularity has surpassed expectations. The case for investment was based on the value of travel time savings to users (business, commuting and leisure) plus a number of wider economic impacts (mainly agglomeration benefits). The value of time saving benefits was put at some £12 billion, while the wider impacts provided an additional £7 billion in 2005. Subsequently, further analysis in 2018 increased the wider benefits to £10-£15 billion.

As with HS2, there was no explicit reference in the appraisal to the impact of the new rail route on real estate values or on the economic value of the businesses to be accommodated in new developments along the route. The assumption was that the boost to development and employment was accounted for by the value of travel time savings plus the wider impacts, an assumption that is implausible to non-economists. The economic analysis of the investment case failed to consider the spatial distribution of benefits, although by the very nature of the project, these would be largely within London. Nevertheless, the benefits to businesses were recognised by a funding agreement between the Mayor/TfL and the Government, which identified contributions of £300m from ‘developer contributions’ and a further £300m from a ‘London Planning Charge’ (subsequently to become the Mayor’s Community Infrastructure Levy or MCIL), a useful but not decisive contribution.

Transport for London has developed a framework to evaluate the benefits of the Crossrail investment. It is envisaged that a study to be published two years after opening will address the transport effects of the new railway, including: mode shift from cars to public transport, relief of congestion on public transport and roads, and the implications for air pollution and carbon emissions. A subsequent study is planned to consider the broader social and economic effects, including the effect of improved connectivity on new homes and jobs, changing patterns of employment and land use, and residential and commercial property prices. A report has already been published on the pre-opening impacts of Crossrail on property prices, arising from the announcement of the project; this found fairly small positive increases to both house prices and office rents.

TfL’s approach to evaluation is admirably ambitious, yet there is obvious inconsistency with the original investment case based on the value of estimated travel time savings and of wider impacts inferred from econometric analysis. It seems unlikely that it will possible to compare forecast and outturn by deducing time savings and agglomeration benefits from the evaluation findings. This prompts the question of whether, with hindsight, the investment appraisal could have been based on projections of the actual benefits that are expected to be achieved. Certainly, inconsistency of economic analysis as between appraisal and evaluation does not make much sense, not least because ex ante travel time savings and wider impacts are, by their nature, notional not observable.

A comparison with the Northern Line Extension

The possibility of forecasting the actual expected benefits of investment is illustrated by another London rail investment, the Northern Line Extension to a large brownfield site comprising the derelict Battersea Power Station and adjacent erstwhile low value commercial buildings and opportunity sites. The developers took the view that the optimal commercial gain would result from access to new properties on the site by means of an extension to the Underground, rather than by enhanced surface modes. The Battersea developers were therefore willing to contribute a quarter of the construction cost in cash. The Treasury agreed that additional taxes paid by businesses locating to the area would contribute the remainder of the financing of the rail link. On that basis, TfL could agree to proceed with construction, a rare instance of the capture of increased land value arising from new transport infrastructure to finance that infrastructure. Views may differ about the quality and coherence of the subsequent development, yet a significant area of central London has been transformed from low value to high value property, including a new building for the US Embassy.

It is relevant that there had earlier been a standard economic appraisal of transport user benefits for a range of alternative property and transport investments on this site, where the predominant benefits were travel time savings. It was found that extension of the Underground would have a less favourable benefit-cost ratio than other transport alternatives on account of the higher capital cost. Nevertheless, the decision was made to extend the Tube, the increase in real estate value being the deciding factor. Thus, much as with earlier development of the Underground, for instance the pre-war extension of the Metropolitan line, the decision was taken essentially on a commercial basis, with the estimated increase in real estate value forming an integral element of the investment decision. This exemplifies the scope for a transport authority working with a developer to take into account the value of real estate improvement for mutual benefit to take into account the increase in real estate values. In this case, of an underground electric railway, detrimental externalities were not important beyond the construction phase.

Conclusions

The main message from these reflections is that there are fundamental shortcomings to orthodox transport investment appraisal, as set down in the Department for Transport’s Transport Analysis Guidance (TAG). These arise principally from a requirement to requirement to estimate economic benefits based predominantly on time savings and other user benefits that are notional, not real and observable; the disregard of changes in land use and value that results from the improved access made possible by transport investment; and the lack of any mechanism to recognise the spatial and demographic distribution of benefits, a crucial concern in the context of regional disparities and avowed intentions to level up society. As exemplified by the cases discussed above, the orthodox approach is not fit for purpose and is becoming irrelevant for decisions making. This leaves political and commercial actors to call the shots.

These shortcomings are all the worse, given that there has been emphasis in the last two years, both in the Treasury’s Green Book and in TAG, on articulating the strategic case for a transport investment. The requirement is to set out a robust case for change that demonstrates how a proposal has a strong strategic fit to the organisation’s priorities and government ambitions. There were successive attempts to do this for HS2, clearly none wholly convincing, leaving observers with a feeling that the goal posts were being continuously moved. And now, consequent to cancellation, there is little sense of any strategic thinking, informed by cogent economic analysis, in the mishmash of investments and interventions announced by the Prime Minister, seemingly to avoid being accused of truncating HS2 merely to save money, and perhaps to find a more politically acceptable set of beneficiaries in the short term.

It is time for the DfT economists to desist from engaging in the incremental development of their thousand pages of TAG. Rather, they need to stand back and ask what purpose is being served by this, when decision makers evidently have quite unrelated preoccupations. The necessary shift in mindset is to recognise that the role of transport investment in generating economically transformational change depends on interlinked decisions by local political leaders, planners, developers and transport authorities, as illustrated by the Northern Line Extension. Appraisal needs to take a holistic view of economic benefits, including from development. The current methodological practice of focusing on transport user benefits in the absence of such linked decision-making means that the uncertainties about ultimate economic benefits are either too great to allow funds to be committed in the first place, or risk having the plug pulled after construction has started if costs increase, as illustrated by HS2.

The above blog was the basis for an article in Local Transport Today of 17 October 2023.