The National Infrastructure Commission published its Second National Infrastructure Assessment on 18 October. The Commission’s objectives, set by the Government when it was established in 2015, are to support sustainable economic growth across all regions of the UK, improve competitiveness, improve quality of life, support climate resilience and transition to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, all within a specified long-term funding envelope for its recommendations.

The NIC’s remit is to issue a comprehensive analysis of the UK’s infrastructure requirements once every five years. This covers all economic infrastructure sectors, setting out recommendations for transport, energy, water and wastewater, flood resilience, digital connectivity and solid waste. The Assessment takes a 30-year view of the infrastructure needs within UK government competence and identifies the policies and funding to meet them.

First, I will look at some of the key conclusions and recommendations concerning transport from the NIC’s analysis, which should be fairly uncontentious, at least for transport planners and practitioners:

- The public transport networks of England’s largest cities under-perform relative to comparable European cities. Initial priorities for investment should be in Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds and Manchester and their wider city regions, to prevent growth being constrained. The scale of capacity increases required justifies investment in rail- or tram-based projects. The government should make financial support conditional on cities committing to introduce demand management measures to reduce car journeys in city centres, and cities should provide a contribution of at least 15-25% to the funding of large projects, whether from fiscal devolution or transport user charging.

- Transport budgets should be devolved to all local authorities responsible for strategic transport so that all places are able to maintain existing infrastructure – for example improving the condition of road surfaces – and invest for local growth. This will also help places develop locally led infrastructure strategies through which transport investment can be considered against long term goals and planned alongside housing and land use development.

- For the national road and rail networks, the government’s first priority should be to maintain existing networks by investing adequately in maintenance and renewal, including ensuring resilience to climate change impacts.

- In order to align the processes of road and rail capital investment, the government should set a long-term investment pipeline across road and rail around an indicative total budget envelope and with clear common strategic objectives. This should incorporate a strategic vision for the main transport corridors that includes both road and rail, ensuring that they are considered together and not separately.

The NIC goes on to say that the cancellation of HS2 beyond Birmingham, which happened only at the beginning of October, after the Assessment had been completed, leaves a major gap in the UK’s rail strategy around which a number of cities have based their economic growth plans. A new comprehensive, long term and fully costed plan is needed, says the Commission, to set out how rail improvements will address the capacity and connectivity challenges facing city regions in the North and Midlands. Who could argue with that?

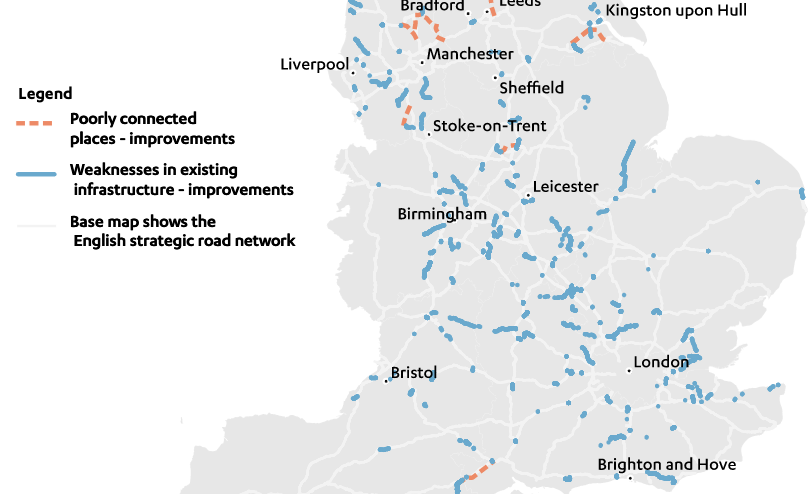

More problematic, in my view, is the NIC ‘s proposition that the government should plan and invest in enhancements to the road network, targeting under-performing sections that can facilitate trade in goods, and provide better connections between cities to facilitate trade in services, observing that it is not clear that this happens at present. Accordingly, the NIC has developed a portfolio of road enhancement options, based on a connectivity metric developed by consultants, that gives each place in Britain a score to denote how well connected it is to other places, calculated by taking the average travel time between a given place and other places in Britain, and weighting them by population and distance, which are useful indicators of likely demand for travel between places. This approach is used to identify the worst performing routes on the network with substantial demand potential between key cities and towns (see map in illustration). The portfolio has been developed within a proposed budget for road investment to cover the next 20 to 30 years.

In support of its proposals for road investments, the Commission states that better connectivity will help improve trade efficiency, making it easier for businesses to move freight and trade goods and services. However, the evidence for this is problematical. For instance, one source cited by the NIC concludes that for an inter-regional transport investment, economic activity may shift either to the lower productivity region (the periphery) or to the higher productivity region (the core), the outcome depending on the underlying economic conditions and the type and scope of the investment. This is known as the Two-way Road Effect.

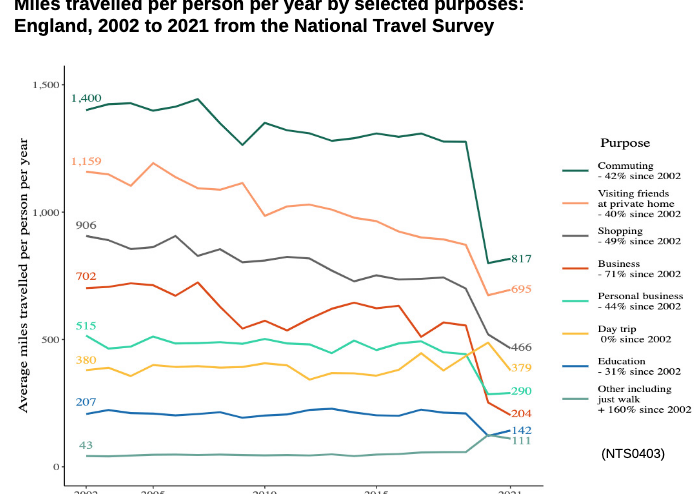

The emphasis of the NIC ‘s analysis is on trade in goods and services, only indirectly on non-business travel. Yet adding capacity to road and rail routes accommodates and generates more use of all kinds. On motorways, for instance, there is evidence that the increased capacity arising from converting the hard shoulder to a running lane results in local users, commuters and others, diverting to take advantage of a faster journey, pre-empting capacity intended for longer distance business users. A low connectivity metric score may well arise from delays due to morning and evening traffic congestion, indicating the existence of substantial car-based commuting. This suggests that enhancement of capacity could be expected to further increase in use by commuters, with little benefit to trade in goods and services. So, I would contend, the NIC’s approach to connectivity is too simplistic.

A further problem with the NIC’s analysis is that although it recognises that road investment will need to be compatible with plans to decarbonise transport, it concludes that the additional emissions from its proposals will not themselves substantially alter the scale of the challenge (which must therefore be borne by the plan to achieve widespread vehicle electrification by 2035). This conclusion is based on embracing the Department for Transport’s projections of road traffic demand growth of 10-28% by 2035 (as indicated in the DfT Decarbonisation Plan), while a road enhancement programme over that period would be expected to increase demand by only around 0.6 to 1.3% (based on historic evidence from a number of studies).

However, the rule of thumb, based on general experience, is that we cannot build our way out of congestion, so any increase in capacity will result in more journeys (good for trade), it will also mean more traffic, resulting in more carbon emissions – at least until fossil fuels are eliminated from road transport – and restoring congestion to what it had been (not good for trade). The Commission’s analysis, suggesting that the additional carbon emissions from its road investment proposals are relatively small, is unconvincing. What is missing is an estimate of the total additional carbon emissions from its programme of road investment, to be compared with the DfT Decarbonisation Plan projection of 620-850 MtCO2 savings from vehicle electrification between 2020 and 2050. If the total additional carbon emissions from the proposed road investments turns out to be relatively small, this implies relatively little benefits to trade; if they are large relative to the impact of vehicle electrification, then the pathway to net zero is put at risk.

A lacuna in the Commission’s analysis of transport infrastructure investment more generally is the failure to consider the application of digital technologies, both to the highway network and the vehicles using it, to enhance the performance of the system overall. The exemplar for this is the application of digital signalling on the railways that allows shorter headways between trains at peak times, thus increasing the capacity of existing track.

Conclusion

I had high hopes for the NIC as an alternative source of policy advice and appraisal methodology when it was set up in 2015. Its analysis of rail investments for the Midlands and North of England offered fresh thinking and was influential in shaping the Government’s plans published in 2021. But the Commission’s proposals for road investment are disappointing, both as regards methodology and conclusions. I suspect at least part of the problem is that its efforts are spread across the whole range of infrastructure investment it is required to cover, so that there is too little capability for deep thinking about how the road network functions and how additional capacity impacts on performance. The NIC needs to develop better models, methodologies and data sources if it to offer fresh thinking for road investment and challenge conventional wisdom and assumptions. If not to provide fresh thinking to that hitherto applied by the DfT, what is the purpose and benefit of the Commission?

Moreover, the Commission was badly unsighted by the Prime Minister’s announcement of the truncation of HS2. The failure of the Government to engage with it on such a major decision prompts a question about the purpose and status of the Commission. The politically-driven redistribution of the funds allocated to HS2 to local transport schemes is quite contradictory to the long term analytically-driven approach that is the remit of the NIC. So, while in principle, analysis of long term requirements for infrastructure investment must be right, in practice short term budgetary constraints and political priorities can render the long view nugatory. One has to ask whether there is a future for the NIC.

A Labour government might well be more sympathetic to the NIC’s role, given that the party in opposition in 2012 established a review of infrastructure planning under Sir John Armitt, now chair of the NIC. That review indeed proposed a National Infrastructure Commission be established. Labour has plans for major capital investment to support the transition to net zero, so having a source of independent advice on such expenditure may be continue to be attractive.

Indeed, there may be a case for merging the NIC with the Climate Change Committee, given the overlap of functions and their cross-departmental approach to future demand and supply. Yet as long as individual departments and their ministers retain responsibility for their budgets and spending plans, with the associated tendency to take a short term view, the strategic may continue to be subordinate to the politically pragmatic.

This blog post was the basis for an article in Local Transport Today of 28 November 2023