I have previously discussed the widening of the M25 motorway between Junctions 23 and 27, where the economic benefits forecast did not materialise. Another example has now arisen.

Conversion of the hard shoulder of the J10-13 section of the M1 motorway to dynamic running was intended to reduce congestion by allowing the hard shoulder to be used as an additional running lane during busy periods. The scheme, one of the earlier ‘smart motorways’, opened in 2012 and a report of its first five years of operation, up to 2017, was published in 2021. The cost was £489m for 15 miles of widened motorway, adjacent to Luton, to the north of London.

Electronic signs tell drivers when it is safe to use the hard shoulder as a running lane, but then speeds are limited by the level of congestion, with a maximum of 60mph. This, together with some traffic growth on the route, meant that journey times were in fact longer than before the road was converted.

The main economic benefit of road investments is taken to be travel time savings. In the present case, the forecast had been for an average travel time savings of 1.5 min per vehicle in the opening year, increasing to 2.25 min by 2028. But time savings were not observed. The forecast benefit-cost ratio (BCR) had been 1.4, whereas the estimate based on the five-year outturn was negative, -0.8.

The stated conclusion, five years after opening, was: ‘In this case, the monetisation of journey time benefit is not a good measure of value for money and the qualitative evidence presented in the evaluation is considered a more robust measure.’ The failure of forecasting was attributed to limited prior experience of such smart motorway conversions.

In view of this marked discrepancy between forecast and outturn, I made a Freedom-of-Information request to see the detailed reports of the traffic modelling and economic analysis of the proposed investment. The original modelling had been for a widening from three to four standard lanes in each direction. The model was adapted for the use of the hard shoulder for the extra lane. The model drew upon the East of England Regional Model, a variable demand model, for data to input to a local traffic model for the section of the M1 involved. As elsewhere, the traffic modelling employed the established SATURN package.

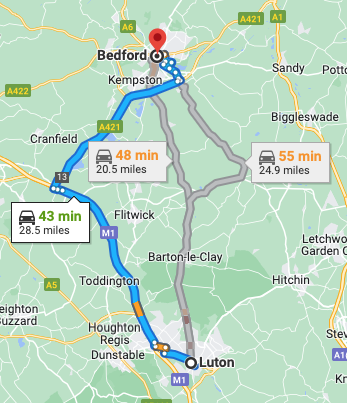

The traffic modelling projected increased traffic volumes, comparing the investment case with the ‘do minimum’ case without the investment, as well as journey time reductions in the range 4-15% for the opening year, depending on section of the road and time of day. The economic appraisal used the output of the traffic model as input to the standard TUBA economic model to project the economic benefits. The main benefits were time savings to business users of £456m pv, offset by increased vehicle operating costs (VOC) of £61m. There were time savings to consumers of £170m, more than offset by increased VOC of £197m. This suggests that the increased road capacity is attracting local users, such as commuters, who save a few minutes of their journey by rerouting to the motorway, at the cost of more fuel use for a longer trip, as illustrated in the screenshot from Google Maps above. A similar situation arose in the M25 case.

The forecast BCR from the TUBA model was 3.5, which is different from the forecast of 1.4 provided in the year five report (above), apparently on account of a change in how increases in revenue from fuel taxation are required to be treated, whether as offsetting the scheme costs or as an element of the benefits from the investment.

Conclusion

Transport models are complex and opaque. Generally, little effort is made to valid forecast against outturn. The present M1 case demonstrates a marked failure of a model to forecast the observed traffic flows and speeds five years after opening.

More generally, monitoring traffic flows and speeds provides only limited information about the validity of a model that projects economic benefits for different classes of road user. The outturn of a widening scheme that matched projected flows might arise if all the increase in traffic volumes arose from more local users taking advantage of the increased capacity to save time on local trips, thereby pre-empting benefits to long distance business users. Effective monitoring needs to track the travel behaviour of different classes of road users.

It seems likely that there is often a bias in traffic modelling of road investments to underestimate the growth of local traffic and hence to overstate the economic benefits to business users.

[…] to what they had been before opening on account of greater traffic volumes than forecast. For the M1 J10-13 scheme, traffic speeds five years after opening were lower than before opening. Since the main economic […]

[…] capacity. I have analysed two Smart Motorway investments in detail: M25 Junctions 23-27 and M1 Junctions 10-13. The Smart Motorway concept involves converting the hard shoulder to a running lane, originally […]