Professor Glenn Lyons has been developing the concept of Triple Access Planning over the past decade and has now published, with 17 co-authors, a 130-page Handbook setting out the approach in some detail. The essential idea is that nowadays we seek access to other people and places by three means: spatial proximity, physical mobility and digital connectivity, each employed to different degrees to meet our needs. Accordingly, if transport planners consider only the transport system, they are ‘dangerously blinkered’ and invite uncertainty into decision making by ignoring the other two systems, it is contended.

The focus on access (or accessibility) as the real objective, rather than movement, is very welcome as an approach to planning. Access is what we seek – to people and places, activities, services and employment, friends and family, for the opportunities and choice that improve the quality of our lives. Over the past two centuries, physical access using mechanised transport systems based on fossil fuel energy arrived with the Industrial Revolution and was rapidly developed, indeed was economically and socially transformational – though not without damage. Next came telecommunication, latterly offering apparently limitless digital connectivity, again having a revolutionary impact. Meanwhile changes in how land is used and the locations of activities relative to one another has reshaped the world out of all recognition.

There can be little dispute that the ‘three option’ thinking is very useful in putting transport provision itself in its proper place. Yet the Triple Access Planning approach, as set out in the new Handbook, has its limitations.

Triple Access Planning is stated to be a way of thinking that marks a change for transport planning from the ‘predict and provide’ paradigm to ‘decide and provide’. This is a fashionable shift of perspective, described as a ‘vision-led’ philosophy, for which there are good arguments in respect of addressing emergent issues such as sustainability. Yet the question avoided is whose vision, and who decides? The answer presumably is that of planners, and of the politicians they serve, both national and local, but who must nevertheless take account of the views of those whose taxes pay their salaries and who elect them into office. The democratic process often impedes the deployment of measures that planners would see as beneficial to the community, but which many members of the public may see as detrimental to their personal well-being, particularly if less car use is proposed. For instance, the Handbook cites as sound thinking the Scottish Government’s Climate Change Plan of 2020 that made a commitment to a 20% reduction in car kilometres travelled by 2030 compared to pre-pandemic levels – an example of decide and provide, but one for which measures to implement such a substantial change have not been articulated. Generally, the Triple Access approach seems designed for planners and has comparatively little to say about the practicalities of gaining general public support for its proposals.

A second, and more substantial limitation of Triple Access Planning is the lack of economic content. Resources are always constrained, so that planners and politicians have to be concerned with the relative cost-effectiveness of different approaches to meeting access needs and their wider consequences.

There is quite a lot that can be said about cost-effectiveness of measures to enhance the three components of Triple Access Planning. Spatial proximity is very largely determined by the built environment we have inherited, whether the low densities of sprawling US cities such as Los Angeles, or the high densities of admired inner areas of European cities like Paris or Barcelona. Generally, UK cities are relatively low density, reflecting a preference for single family homes with gardens. While there is scope for what is called ‘gentle densification’ of existing communities, we could not afford, nor would we wish, to attempt large scale redevelopment of suburbs to higher density. The historic development of British cities therefore limits the opportunity to enhance spatial proximity.

On the other hand, enhanced spatial proximity is an option for some types of new build, for instance based on high rise apartments on urban brownfield sites. However, for new greenfield housing at low density, built to sell by developers, lack of spatial proximity seems not to be seen by purchasers as a disadvantage, although campaigners remonstrate at the lack of alternatives to the car. Occasionally, wholly new settlements might be created, as exemplified by Britain’s Post-War New Towns, the last of which, Milton Keynes, was designed to accommodate the growing car ownership of that era. Subsequently, Poundbury, an urban extension on the western outskirts of Dorchester masterminded by the Duchy of Cornwall (led by the then Prince of Wales), was designed as a walkable community, giving priority to people rather than to cars. Nevertheless, because Poundbury is small – 5,000 homes are planned – the mismatch between homes and jobs means that residents are likely to travel further afield for work, such that car ownership is higher than in Dorchester and the surrounding region, with 55% of residents using a car or van to get to work.

New built homes increase the national housing stock by only about one per cent a year, so it is the existing built environment, homes and facilities, within which almost all trip origins and destinations occur, that places a limit on improving spatial proximity, with little scope for cost-effective change.

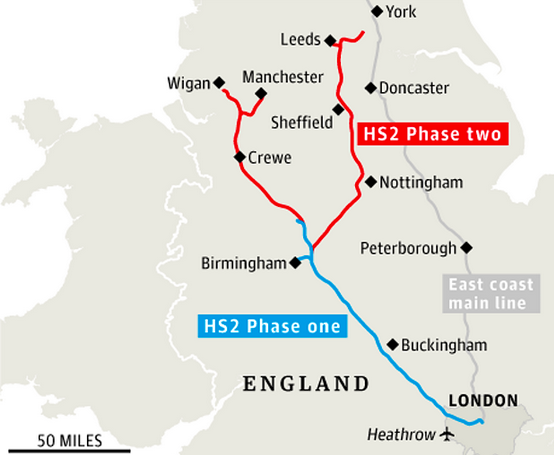

Physical mobility meanwhile depends on the historic transport infrastructure already in place that accommodates all trips. There is much debate about adding capacity to the road and rail networks, and considerable public resources have been allocated for this purpose by successive governments. Yet adding capacity is costly, whether shifting earth, pouring concrete and rolling tarmac for new roads, or constructing track, tunnels, power supplies and signalling for new rail routes, so that the net addition to capacity is quite small. For the strategic road network, annual additional lane-miles barely keeps up with population growth. And for rail, the prospect of escalating construction costs may lead to truncation of plans, as with HS2, or to an unwillingness of decision makers to commit public money in the first place.

So the possibilities for cost-effectively increasing the physical capacity of transport infrastructure to enhance mobility are quite constrained. However, there is scope for making better use of existing networks by means of digital technologies, thereby increasing access, particularly on the railways where modern signalling and control technologies allow higher train frequencies to be achieved while maintaining safety standards. Digital technologies to increase effective road capacity are more difficult to implement, given the diversity of traffic, but warrant more attention than they are receiving, particularly to exploit the very general use by drivers of digital navigation, known as satnav in the road context. But in any event, higher speeds of travel are unlikely to be achievable by digital or other new mobility technologies, which limits increased access by physical mobility, given the constraints on the time available for travel within the 24-hour day.

Enhancing access by improved digital connectivity seems a more promising approach, given the scalability of the relevant rapidly advancing technologies and the resulting cost reduction, hence the ubiquity of digital connectivity, driven by Wi-Fi and Broadband that have facilitated a variety of telecom innovations and apps for online interaction, such as Zoom or Teams, and services such as Skype and FaceTime, as well as social media sharing and conversational networks, all at an affordable cost.

So enhanced access through the new digital technologies is a persuasive approach in theory, but what about the practice?

There has been a long-running but inconclusive debate about whether digital communications technologies can and will actually substitute for physical mobility, or instead mainly complement it, for instance by allowing people to cultivate wider social and business networks, with whom face to face contact from time to time would be important to sustain relationships, and the parallel desire to undertake ‘experiential’ activity through leisure travel. The forced cessation of travel during the coronavirus pandemic showed that we could make much more use of digital communications than we had previously. Although travel behaviour has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels for all modes, it has come fairly close, and indeed sometimes exceeding prior levels, particularly car use and air travel. In respect of the journey to work, the tensions between desires of employees to work from home for part of the week, and the wish of their managers to have them in the workplace, seem not to have yet fully played out. But in any event, it would be hard to conclude that the desire for face-to-face access has changed substantially, let alone being in decline, despite the availability of cost-effective digital technologies that make remote personal interactions possible.

The pandemic also led to a boost to online retail, but subsequently growth returned to the prior trend. Much shopping is a social and hands-on activity, so a new balance will emerge between the physical and the virtual – perhaps in the quite near future. Yet public policy is focused on sustaining the vibrancy of town centres, not promoting digital connectivity as an alternative to bricks-and-mortar retail. More generally, digital technologies may be comparatively low cost compared to physical structures, yet cost-effectiveness requires the utility of digital technologies for access purposes to be assessed in comparison with physical mobility – with the outcome still to be determined. The comparative carbon footprint of electricity-driven digital activity compared with physical mobility, and its own shift to electric power, is similarly far from yet clear.

The Triple Access concept is welcome in that it encourages wide ranging thinking about the possibilities for meeting people’s needs for access. Yet when an assessment of the cost-effectiveness of measures that might be adopted is superimposed, the scope for implementing innovative measures becomes quite constrained.

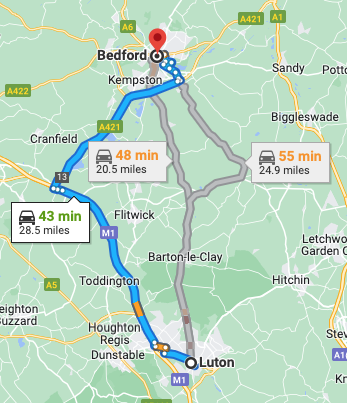

A third limitation of the Triple Access approach is the lack of consideration of the basic characteristic of access, which is that it is subject to diminishing returns – the more access you have to any kind of service, the less the value of a further increment. The Competition Commission, as it then was, some years ago investigated competition between the main supermarket brands. This involved relating where people lived from census data to where the large supermarkets with car parking were located, finding that 80% of the urban population had three or more supermarkets within 15 minutes’ drive, and 60% had four or more – arguably offering good levels of choice. You could ask yourself whether you would need to drive further to have more choice in the weekly shop – if not, your demand for travel to supermarkets would be said to have ‘saturated’. This has come about over the years through growing household car ownership and investment by the supermarket chains in more large stores, both trends now largely played out.

For those who don’t run a car and rely on local food stores, similar developments have been widely seen, with the main chains opening small local branches and many thriving independent minimarkets staying open for conveniently long hours. In my own neighbourhood, for instance, in an inner London borough, there are branches of two chains and some four independents, all within ten minutes’ walk. However, there remain ‘food deserts’ in areas of low income where choice of outlets is limited.

How much shopping choice we need depends on the nature of the goods or services we seek. For standard products at fixed price, such as newspapers, the nearest shop suffices. For fashion goods, a trip to the city centre may be justified, plus a search of online outlets. Many services are routinely purchased online, insurance in all its forms, for instance, and much travel booking.

A second characteristic of access is that it increases, approximately, with the square of the speed of travel: what is accessible is proportional to the area of a circle whose radius is proportional to the speed of travel (recalling elementary geometry). A constraint is the density of the road network, highest in urban areas, lower in rural. But in any event, access increased markedly as car use replaced slower modes. It is the combination of access increasing with up to the square of the speed of travel while being subject to diminishing returns implies an expectation of the saturation of travel demand to achieve access to frequently used activities.

In practice, those who have available use of a car and/or good public transport provision, plus fast broadband, arguably have sufficient access to sources of most goods and services to meet their needs, implying that their demand for access has saturated. Demand saturation is a phenomenon that arises generally once uptake of some new innovation is widespread, washing machines for instance where the market now depends on replacement of worn-out models plus population growth. There is no reason to suppose that demand saturation would not apply to travel, although it is a topic neglected by investigators and theorists.

In conclusion, while Triple Access Planning encourages fresh thinking, the constraints on practical measures, and the circumstances in which these might be applied, seem thus far to have been underestimated. Limiting factors are insufficient consideration of public aversion to change, the cost-effectiveness of measures that might be adopted, and the fundamental characteristics of access benefits. Nevertheless, the aim of meeting the human need for access by means other than investment in transport infrastructure is a welcome extension to conventional transport planning and analysis that deserves further development.

This blog post is the basis for an article published in Local Transport Today 2 July 2024.