I gave a talk on this topic at a recent meeting of the Transport Economists Group, one theme of which was the subject of the previous article. My overall conclusions are set out below.

A number of new trends emerged in the 1990s, or in some cases are still emerging:

- There has been no growth in average distance travelled in Britain for more than 20 years, whether by all surface modes or by car alone. Available data suggests that this holds for the developed economies generally. This contrasts with the previous century and more during which average distance travelled increased steadily.

- One reason for this cessation of growth of distance travelled lies in technological constraints on faster travel. We cannot drive faster on the roads, safely and with acceptable emissions. We have high speed rail to come, but rail is responsible for a minority of trips, and high speed rail for a minority of a minority. These technological constraints mark the end of an era that began in 1830 with the first passenger railway, which harnessed the energy of fossil fuel to permit travel at faster than walking pace.

- Car-based mobility or access to good public transport allow high levels of choice of many regularly used types of destination, thus lessening the need to travel further.

- Travel demand per capita has ceased to be driven by growing incomes. Total travel demand is now determined largely by population growth. However, the pattern of such demand will depend on where the additional inhabitants are housed – if on greenfield sites, more car use; if within existing urban areas at higher density, then more public transport.

- Car use in big cities has passed its peak, in term of mode share, and is now declining. Successful cities attract people to work, study and live, so population density increases. The city authorities recognise that the road network cannot be enlarged to accommodate increasing car use, so investment in urban rail is needed to meet the mobility needs of the population.

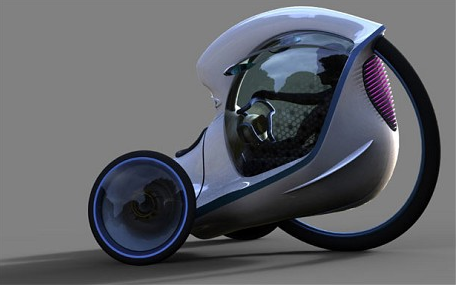

So travel in the twenty-first century will be different from travel in the twentieth century, quite apart from the impact of technological developments such as driverless cars.

In contrast to these new trends, one unchanging feature is average travel time of about an hour a day, found for all settled human populations. This constitutes a sound basis for forecasts or scenarios of future travel. Travel/transport models should be constrained to hold average travel time constant in the long run. They also need to recognise the new trends outlined above as regards both model structure and calibration. Most existing models are obsolete.