I have a new book published on 1 September, one in a series of short books on policy and economics topics described as ‘essays on big ideas by leading writers’. My contribution is a critique of the inconsistencies of transport policy in recent decades, which I attribute to the shortcomings of conventional transport economic appraisal in identifying the benefits that arise from investment. A column in The Spectator magazine of 26 September described my book as ‘excellent throughout’. My book, Travel Fast or Smart?, is available both in print and as an ebook from Amazon Books.

Nottingham is a city unique in Britain in that it has taken advantage of national legislation, the Transport Act 2000, to introduce a Workplace Parking Levy. The consequences have been outlined in a helpful brief prepared by the Campaign for Better Transport.

Nottingham is a medium sized city with two universities and a tram system. The Levy was implemented in 2012 and applies to employers providing 11 or more parking places for employees, who must pay £375 per place per year. There are 42,000 workplace parking spaces in the city, of which 25,000 are chargeable. Operation of the levy is quite low cost.

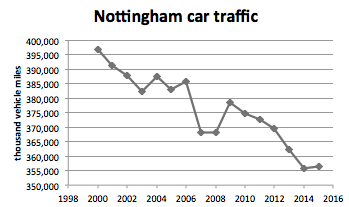

The direct impact of the levy is to reduce car commuting, reinforcing the declining trend in car traffic shown in the Figure. The revenue of £25m raised in the first three years is ring-fenced for transport improvements, the indirect impact, for instance to help fund doubling to coverage of the tram network.

Assessment

Big cities like London, with dynamic economies and growing populations, are experiencing a declining share of journeys by car, as they invest in rail for speedy and reliable travel for commuters. A declining share for the car is associated with increasing prosperity, at least in big cities. But what of smaller cities? Do they do best by attempting to accommodate the car, the traditional approach? Or should they push back the cars, which impede economic, cultural and social interactions that make cities good places to live?

Nottingham’s experience suggests that bearing down on car commuting may make a useful contribution, even though it requires brave politicians to push through a Workplace Parking Levy against the inevitable initial opposition. The Levy has particular virtues: it impacts only on residents, not on visitors from out of town, who may have available competing destinations for shopping and leisure activities; and because it reduces car commuting, it makes more road space available for buses at peak times.

Encouragingly, Nottingham ranked top in 2016 in the National Highways & Transport Network Satisfaction Survey carried out in 106 local authority areas by Ipsos MORI.