The RAC Foundation has published a report on how information can be conveyed to drivers via connected vehicles. This assessed representative possibilities including In-Vehicles Signage (IVS) to display road signs and warnings to the driver inside the vehicle, and Green Light Optimal Speed Advisory (GLOSA) which tells drivers what speed to adopt to pass through the next set of traffic signals on green. The report discussed the obstacles to implementing these technologies, which it suggested arise mostly from organisational, institutional and human issues.

What was not adequately considered was the elephant in the room – the existing digital navigation (satnav) services, whether available free of charge as smartphone apps (Google Maps, Waze and others) or embedded as an integral part of the vehicle equipment. While the report mentions satnav devices as already providing some signage information, it envisages that a key element of the IVS concept is the ability for highway authorities to communicate directly with drivers, so that they can give them information they want them to receive (for example hazard warnings), as opposed to a satnav provider generating messages themselves.

Yet given the widespread use of digital navigation, it seems likely that the prime deciders of what information is conveyed to drivers will continue to be the satnav providers, not the highway authorities. The latter would need to make timely information available to the former if drivers are to benefit. But while highway authorities are subject to statutory regulation, providers of digital navigation are unregulated and are free to choose what information to provide to road users.

More generally, digital navigation has transformed how very many motorists use the road network, particularly for occasional, as opposed to regular, journeys. A choice of routes is offered at the outset of the trip, with estimated journey times, which mitigates the main perceived problem with traffic congestion – the uncertainty of time of arrival. Alternatives may be offered en route in response to the build-up of congestion. However, because the service providers of digital navigation are very secretive about their methodologies, we have little idea of the impact of their guidance on the overall functioning of the road network. For instance, we do not know if the rerouting in response to a crash on a motorway is optimal for users of the whole road network, or for drivers responding to the advice, or for neither.

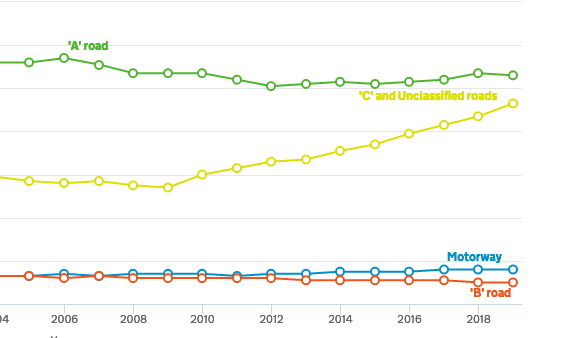

There have been many anecdotal reports of digital navigation resulting in problematic use of minor roads (‘rat running’). While traffic on A and B class roads in London has been broadly stable since the mid-1990s, traffic on C roads, which had also previously been stable, increased from 5.4 billion miles in 2009 to 9.3 billion in 2019, suggestive of substantial impact of digital navigation devices.

There is clearly a case for better coordination between satnav providers and highway authorities to optimise the impact of digital navigation for all road users and to minimise environmental harms. There is in fact a legal basis for achieving this, although it has not been put into practice. The Road Traffic (Driver Licencing and Information Systems) Act 1989 requires dynamic route guidance systems that take account of traffic conditions to be licenced by the Secretary of State. This was enacted to facilitate the introduction of a pilot route guidance system that had been developed by the Transport Research Laboratory (then part of the Department for Transport), which in the event was not taken forward. A licence could include conditions concerning roads that should not be used and information to be supplied about traffic conditions.

There is a need for a review of the impact of digital navigation on the functioning of the highway system with a view to identifying ways of benefiting road users. It is very likely that exploiting digital technologies would be far more cost effective than employing costly civil engineering technologies to increase capacity.