The Economist magazine of 28 June included an article to mark the 75th anniversary since the launch of Formula One (F1) motor racing at the Silverstone circuit in 1950, and the consequent development of the F1 activity into a very substantial global business, which changed hands for US$8 billion in 2017.

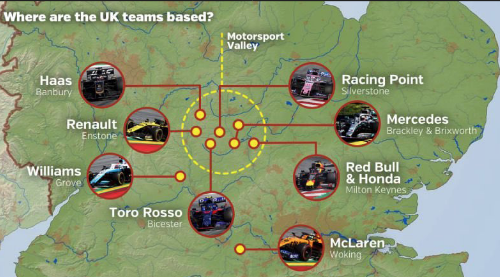

Perhaps surprisingly, seven out of the ten racing car teams competing in F1 are based fully or partly in England, in an area within an hour’s drive of the Silverstone circuit in Northamptonshire, with one or two newcomers expected next year. The competing manufacturers are supported by more than 4,000 companies, from parts suppliers to PR firms, employing 50,000 people in all and generating revenues of £16 billion in 2023. Moreover, the Silverstone Technology Cluster, created in 2017, is a not-for-profit with 150 members that supports business to develop their capabilities. It is often lauded as an example of British industrial achievement and a driver of automotive innovation and technological development.

This highly successful industrial cluster well illustrates the concept of how agglomeration benefits can be gained from learning, sharing and matching. Firms acquire new knowledge by exchanging ideas and information, both formally and informally; they share inputs via common supply chains and infrastructure; and they benefit by matching jobs to workers from a deep pool of labour with relevant skills. Generally, it is supposed, agglomeration benefits drive urban development and population growth at higher densities, despite high land prices, rents, transport and other costs. To support this process, investment in urban and peri-urban transport is seen as helping generate agglomeration benefits.

In contrast, the FI cluster is quite spatially dispersed, and despite being dependent on established road links, there is no suggestion that transport improvements would be critical for further success. This prompts a question about the general relationship between the economic benefits arising from agglomeration and how these might justify transport investment in a modern economy with relatively mature transport systems.

We have had two centuries of investment to build our modern transport system since the opening of the first passenger railway in 1830. This has transformed how we live and work, and where industry and service businesses are located in relation to where the population resides. Over this period, industrial clusters have come and gone, such as textiles, ceramics and shipbuilding, a process that continues in a dynamic economy. It would thus be wise for our beliefs and expectations of what are casual relationships to be critically reviewed in the light of experience.

Another interesting, and now historic, cluster is ‘Fleet Street’, once the physical location of the national newspapers in central London, with printing presses in the basements, print workers on floors above and editorial staff on the upper floors. This was a classic cluster, as I discussed in my recent book (section 3.2), with benefits from shared facilities and staff, allowing news to travel faster and gossip to flourish. Those involved profited by being together, and the transport system was developed to bring them there and take them home, with personal contacts facilitated by short walking distances to the pubs and cafes in the immediate neighbourhood.

But there were offsetting disbenefits: newsprint in the form of huge rolls of paper had to be brought into central London, from where newspapers were distributed across the country overnight, and there were restrictive labour practices reflecting trade union power when the product had to be made anew each day. However, by the latter part of the last century the advent of digital typesetting allowed newspapers to be printed at remote printworks with better access to transport networks, so that the editorial offices could disperse to scattered locations around London.

Nowadays, ‘Fleet Steet’ is a metaphor for the newspaper industry, no longer the actual location. And the print newspaper industry itself is a shadow of what it was, now eclipsed by the digital online information explosion. With hindsight, the agglomeration benefits and disbenefits were evidently more finely balanced than had been supposed, so that new technology could tilt the balance in favour of dispersion of the cluster.

A similar problem with union militancy in the auto plants of Detroit – of Ford, General Motors and Chrysler – facing competition from Japanese manufacturers, led to the dispersal of the industry cluster to other parts of the US where the United Auto Workers Union found it difficult to organise. The population of the Motor City fell from 1.8 million in 1950 to 0.6 million in 2020.

Another London cluster, this one of recent development, is the financial services concentration in and around Canary Wharf in Docklands. London was once the world’s largest port, but the traditional wharves and warehouses were made obsolete by the advent of containers carried in large ships that the existing docks could not accommodate, which went instead to berths downriver and to new coastal ports like Felixstowe.

A key initiative in redevelopment of the area was construction of the Docklands Light Railway (DLR), which connected the Docklands with the City, a relatively inexpensive development that relied on reusing disused railway infrastructure and derelict land for much of its length, employing smaller driverless rolling stock, compared with standard urban metros. The DLR showed how accessible was Canary Wharf – currently 10 minutes from Bank Station – and stimulated the development of a new financial quarter, both to complement and compete with the historic ‘square mile’ of the City of London. Growth of Canary Wharf was furthered by a succession of rail investments: the Jubilee Line Extension, the Overground, and most recently the Elizabeth Line that provides a direct link to Heathrow Airport.

The coronavirus pandemic generated an unanticipated stress test of the agglomeration benefits associated with the Canary Wharf cluster, as many employees were required to work from home, fully or partly. The development of fast broadband connectivity and software suitable for home working and remote meetings allowed dispersal of individuals from traditional workplaces, which employees liked more than their managers. The resulting tensions are still being played out, with a continued drift back to the offices, but resisted by those preferring to work from home.

After three decades, initial long leases at Canary Wharf are coming up to their expiry dates and the first cluster of buildings, conceived in the late 1980s and early 1990s, have reached an age when everything from windows to elevators and air conditioners will need expensive upgrades. Some large occupants have decided to move back to the City, while others are downsizing their space requirements. Property investors will have to commit huge sums to breathe fresh life into these buildings and revitalise the area, with little certainty that their plans will pay off. Shrinkage of this financial services cluster is not beyond the bounds of possibility, a consequence of the fine balance between pull and push factors, but allowing repurposing of existing buildings to respond to other commercial opportunities.

Residential developments in Docklands illustrate what would once have been unimaginable – our current affection for ‘waterfront living’ that has made homes alongside the river a highly desirable category of property – unthinkable to those forced to inhabit slums by the polluted Thames of the Victoria era.

Similar changes are evident elsewhere. New York City was also a historic major port for both cargo and passenger liners, which became obsolete like London. An elevated freight railway met the needs of the docks on the Hudson River, but lower Manhattan is well served by the subway system, so that the obsolete track could be converted to the High Line, an elevated linear park that has become a popular attraction offering exceptional views of the city and Hudson River, along with art installations, diverse plantings, and public programs.

Reutilisation of obsolete urban rail routes thus offers options for cities, whether to boost connectivity for traditional agglomeration benefits, or to improve the quality and attractiveness of the urban environment, with likely economic benefits for nearby retail businesses and the urban economy as a whole.

A broader approach to consideration of agglomeration benefits involves relating city size to productivity. Many economists argue that larger cities are more productive than smaller cities, and become ever more productive as they grow due to increased agglomeration benefits. However, Britain is exceptional. An OECD study published in 2020 concluded that the level of productivity in a group of 11 large UK second-tier cities (other than London) is low by national and international standards. Second-tier cities in most other large OECD countries have productivity levels that are as high as, or higher than, the national average. However, the gross value added (GVA) per worker in the UK cities was just 86% of the UK average in 2016 and the gap between these and second-tier cities in other OECD countries is even larger (ref 2).

Tom Forth, of Open Innovations (https://open-innovations.org/), has authored influential analysis of the relationship between GDP per capita and population size, of British and comparable non-capital European cities. He finds in general a positive relation between size and productivity. However, almost uniquely among large developed countries, this pattern does not hold in the UK. The UK’s large cities see no significant benefit to productivity from size, especially when London is excluded. The result is that our biggest non-capital cities, Manchester and Birmingham, are significantly less productive than almost all similar-sized cities in Europe, and less productive than much smaller cities such as Edinburgh, Oxford, and Bristol.

According to Tom Forth, one notable difference between the UK’s large cities and those in similar countries is how little public transport infrastructure there is in the UK cities. While France’s second, third and fourth cities have 8 off-street metro lines between them (four in Lyon, two each in Marseille and Lille) the UK’s equivalents have none. Manchester and Lyon have similar-sized tramway systems, with about 100 stations each, but Marseille (3 lines) and Lille (2 lines) have substantially more than Birmingham (1 line) and Leeds (0 lines). Greater reliance of UK cities on buses results in slower journeys, more variable journey times and poorer reliability. Forth argues that people generate the most agglomeration benefits for a city when they travel at peak times, to get to and from work, meetings, and social events, times when buses offer poorer service.

Analysing travel time by bus in Birmingham, Forth finds that 0.9m people could reliably get to the city centre in 30 minutes at peak time, compared to 1.3m off peak, and a simulated 1.7m by tram throughout the day. His hypothesis is that by relying on buses that get caught in congestion at peak times, Birmingham sacrifices significant effective size, and thus agglomeration benefits, to cities like Lyon, which rely on trams and metros. This difference is claimed to explain a significant proportion of the productivity gap between UK large cities and their European equivalents. It also can’t be good for the overall attractiveness of the city as a place to live.

The UK government recently announced investment of £15.6 billion in local transport outside London, largely metros, trams and similar modes. This is consistent with the suggestion that rail-based urban travel can increase productivity. However, as the Centre for Cities points out, British cities are much less dense than European competitors, reflecting our preference to live in houses with gardens rather than apartments – a factor not considered by Tom Forth. This means that fewer people live close to the city centre or near to good public transport connections, both factors that limit what can be achieved by investment in public transport. Increased densification of the existing built environment is difficult to achieve.

Moreover, there is a question about the direction of causality. Could it be that European cities that are more prosperous, for whatever reasons, have more resources to invest in rail-based public transport, the aim being to improve the urban environment by reducing car use in the city centre, rather than to boost productivity?

Consider France, where over the past 35 years, a growing number of cities have developed modern light rail networks – 27 in all, with many of these being extended, while at least seven other municipalities are in the process of planning or acquiring new tram networks. Local authorities are able to fund their own tram and integrated transport systems through the ‘Versement Transport’, a levy on all local businesses that employ more than 11 people. As a legal obligation, the proceeds must be put towards improving the transport system. So the larger and more prosperous the city, the greater the revenue from the levy, which would be an incentive to invest in trams.

I recall a visit some years ago to a friend who lived near Bordeaux. One day we drove to the park-and-ride at the edge of the city and took the tram to the low-traffic centre, where we had a very pleasant day in what is a UNESCO world heritage site. There had been worries that the overhead wires would threaten its integrity, so trams in the city centre are powered by an innovative ground-level power supply system, with a central rail that is only live when the tram is directly over it. Bordeaux is an historic port city, a regional centre of the wine trade based on the many vineyards in its hinterland and an attraction for tourists. While the city is the home to many aerospace businesses, it is far from obvious that the tram system contributes to agglomeration benefits to industry, as opposed to the evident agreeable nature of the urban environment and boosting city centre retail and hospitality.

More generally, the features that make a city an attractive place to live, work, study and visit – a pleasant walkable central area with good leisure facilities, an accessible hinterland for those who wish to escape to a less stressful natural environment, a good ‘cultural offer’, and well curated heritage and public realm – are arguably as important as speedy journeys and traditional physical transport connectivity for those who determine business success and economic prosperity.

Theory

While the examples cited above indicate the variety of ways in which agglomeration benefits might arise (and also lost as circumstances change), the treatment of these benefits in conventional transport investment appraisal is broad brush, based on econometric analysis and possibly outdated metrics.

In the context of DfT’s Transport Analysis Guidance (TAG), ‘wider impacts’ refers to the economic effects of transport investments that are not fully captured by traditional user benefits (mainly time savings). These wider impacts arise from market failures and imperfections, where the full social welfare impact of a transport scheme isn’t reflected in the transport market itself. Such imperfections can lead to changes in productivity, employment, and output in sectors beyond transport. One element of wider impacts reflects the way that productivity is affected by the density of economic activity, which is one of the reasons for the existence of cities and specialised clusters, such as financial hubs. The productivity impacts may occur within or across industries, termed localisation and urbanisation economies respectively, and are known as ‘agglomeration economies’, which are externalities and so are not reflected in transport markets.

Because there is no absolute measure of agglomeration, the academic literature relies on proxies, such as effective density or access to economic mass (ATEM). The DfT uses ATEM as the proxy, which seeks to measure the impact of changes in generalised travel costs and employment location on the strength of an agglomeration, reflecting both localisation and urbanisation effects.

The importance of ‘wider impacts’ was stressed by the seminal 1999 SACTRA report. This led the DfT to adopt a standardised national approach to estimating agglomeration impacts, applying a 10% uplift to business user benefits. However, a 2014 report by Venables, Laird and Overman, commissioned by the DfT, noted that because agglomeration effects cannot be observed directly, benefits have to be estimated indirectly by means of econometric analysis, an approach that lacks context specificity and risks significant errors, not being sufficiently attuned to the specific project that is being studied; more generally, because of the uncertainties, estimation of the scale of wider economic impacts is prone to optimism bias.

This critique appears to have prompted a major elaboration of the relevant guidance (TAG Unit A2-4 productivity impacts) published in May 2025 – a full quarter century since the SACTRA analysis, perhaps reflecting the difficulty of making progress. The 46 pages of guidance includes a requirement to estimate agglomeration benefits either (a) using evidence-based scenarios about how firms and households are likely to respond to the transport improvement or (b) using a land-use model to forecast how the transport scheme would impact firms and households – both challenging tasks prone to optimism bias, I judge.

The new TAG unit appears to have been informed by two recently published studies commissioned by DfT from authors at Imperial College and consultants Arup, but dated June 2024. The first is an account of the conceptual economic framework for treating economic density in transport appraisal, focusing on the modelling required to distinguish user benefits from the consequences of changes in agglomeration that result from transport investment. The economic model of TAG derives the welfare impacts of transport interventions as additive elements that are the outcomes of three partly or fully separated models: (1) a transport model measuring the direct user benefits (DUBs) and transport-related externalities of the intervention, (2) an agglomeration model quantifying the wider agglomeration benefits, and (3) a spatial model measuring other externalities related the relocation of firms and households. The Imperial/ARUP report is technically detailed and discussion is beyond the scope of this article, but the conclusion points to the difficulty of achieving a clean separation between the three elements to avoid double counting of benefits – not obviously attained in the new TAG unit.

One interesting finding of this conceptual paper is that agglomeration effects extend beyond productivity benefits to include amenity and consumption benefits experienced by consumers, higher density development and/or better transport offering more choices and varieties of destinations and services, which could also support the locational choices by the most innovative and creative businesses. This could provide an economic rationale for urban tram systems of the kind found in French cities.

A related paper from the Imperial/ARUP authors is a scoping study for a large-scale re-estimation of the agglomeration parameters applied in TAG, wherein agglomeration impacts for transport schemes are appraised within conventional cost-benefit analysis. Again, this is a thorough technical report, with many themes for further research, which suggest that the DfT would need to think carefully about whether the effort expended in such re-estimation of agglomeration parameters would be cost-effective in respect of improvements to investment appraisal, particularly given this conclusion of the scoping study:

‘The academic literature on transport appraisal has been relatively static in recent years. More significant developments have been made in the urban/spatial economics community, but most of their findings have not been translated into practice-ready solutions for appraisal; and in many cases this task does not seem trivial. Assimilation of this literature in appraisal cannot be part of the scope of a short-term re-estimation of TAG parameters, but it does provide considerable scope for more fundamental research. We recommend that the Department explore the means through which innovation in this heavily policy-relevant field of research can be supported and, if necessary, incentivised.’

The lack of progress in transport economics related to appraisal is a point well made – a matter of diminishing returns to effort and diminishing relevance to policy decisions. In my view, this reflects in part the difficulty of extending the original simplistic approach to cost-benefit analysis to coping with an increasing range of wider impacts beyond the customary benefits to transport users, a consequence of the extensive real-world outcomes of transport investment. The attempt to develop a standard approach to modelling these outcomes is not only inherently complex, as both the new TAG Unit and the scoping study show, but disregards entirely the varied nature of agglomeration clusters, as exemplified by the case studies discussed above.

Agglomeration benefits comprise one element of the outcomes sought from large transformational transport investments for which wider economic impacts are expected tbe greatest. A detailed analysis of 15 case studies of transport investments, seeking evidence of transformational change, concluded that it is rare to find transport investments which, in isolation, change or reverse underlying economic or transport trends, with few instances of benefits realisation strategies being systematically developed to ensure the benefits ultimately materialise, and transformation seemingly requiring private investment to be levered in, potentially at a level several times the level of the original public investment.

Generally, it may be concluded that transport investments considered in isolation cannot be counted on to lead to transformational change, whereas a co-ordinated effort by planners, developers and transport authorities has the potential to change land use on a sufficient scale to be transformational. The creation of New Towns in Britain after the Second World War is an example of transformational change, with Milton Keynes, the last of these, designed to accommodate traffic at a time when car ownership was growing. Another example, the redevelopment of London’s Docklands, depended, albeit in a less co-ordinated way, on a succession of rail schemes – the Docklands Light Railway, the Jubilee Line Extension, the Overground and the Elizabeth Line.

More generally, the fundamental problem with conventional transport investment analysis is the supposition that the main benefit to users is the saving of travel time, time which could be used for more productive work or valued leisure. As I argued in Chapter 4 of my recent book, the evidence is that people take the benefits of faster travel largely as enhanced access to people and places, which provides better outcomes in terms of employment and retail opportunities, lifestyle experience, and available activities in which to engage.

For instance, suppose you live in a village poorly served, if at all, by public transport and you don’t have a car, so you are constrained to use the village shop for groceries and other items stocked. Suppose then you acquire a car. Initially you might continue to use the village shop, using the time saved by travelling by car for other purposes. But you soon realise that with a car, in the time available, you can access the supermarket at the nearby town for a greater variety of goods at likely lower prices. And similarly, when you come to change jobs or move house, the car offers a wider range of possibilities beyond the village, and so country roads fill with traffic. Road authorities may attempt to alleviate road traffic congestion, but the benefits experienced by road users are access benefits, not, beyond the short term, time saving.

Accordingly, to be consistent with observed behaviour, transport investment appraisal should value the projected increase in access, comparing the with- and without-investment cases. Increased access boosts observable land and property values, which can be a useful proxy for access gains.

A relevant example from London is the extension of the Northern Line underground rail route to a large brownfield site at Battersea at a cost of £1 billion, to which the developers contributed a quarter as cash, and additional taxes to be paid by businesses locating to the area allowed Transport for London to borrow the remainder (known as tax incremental financing). The investment decision followed an earlier standard economic appraisal of transport user benefits for a range of alternative property and transport investments, where the predominant benefits were assumed to be travel time savings. It was found that extension of the Underground would have a less favourable benefit–cost ratio than other transport alternatives on account of the higher capital cost. Nevertheless, the decision was made to extend the Tube, the increase in real estate value being the deciding factor. Thus the decision was taken essentially on a commercial basis, with the estimated increase in real estate value forming an integral element of the investment decision, exemplifying the scope for a transport authority working with a developer and the planners to take into account the value of real estate improvement. The agglomeration benefits arising from the enhanced connections were naturally included in the projected property value uplift, both productivity of commercial property and consumer attractions such as the shopping facilities in the renovated and repurposed Battersea Power Station.

Conclusions

Agglomeration benefits manifest themselves in a variety of circumstances, and the balance between pull and push factors can be quite fine, although not apparent in a cluster’s prime years when the positive externalities outweigh the negative. Adoption of new technologies, such as digital type setting or shipping containers, can then suddenly shift the balance.

Efforts to apply standard economic analysis involve a bolt-on to the underlying framework based on the mistaken assumption that time savings are the main benefit of transport investment. Moreover, conceptual consideration of economic analysis of agglomeration benefits shows this to be complex and far from ready for practical application.

In my view, the econometric approach, based on estimation of the notional ‘access to economic mass’, should be abandoned. Instead, there should be effort to test the use of uplift in property values as the observable proxy, working with developers whose practical knowledge and judgment of what appeals to and satisfies customer needs and desires would be a more relevant input than the theories of the transport economists. The impact from planners would also be important, to ensure that developers’ aspirations are consistent with increasing the desirability of the particular place for all who live, work and visit there.

This blog post is the basis for an article in Local Transport Today of 4 September 2025.