I contributed to a recent meeting of the Transport Statistics Users Group to discuss Investment Appraisal. My presentation: Metz TSUG 13-7-16 The main points I made are set out below.

The Department for Transport (DfT) recently commissioned new research to establish monetary values for the saving of travel time. This has served to highlight the problems of using Stated Preference experiments to estimated values of time saved by asking respondents hypothetical questions about the trade-off of time and money costs. Quite a lot of variation in the value of time is found, according to the experimental set up, depending on what other factors are invoked, for instance journey time variability, road congestion or rail crowding; and also whether, for work trips, the perspective is that of the employer or employee. Moreover, an attempt to establish Revealed Preference values, by ascertaining behaviour for rail trips where there was choice of alternative routes, did not succeed for technical reasons. The upshot was new values for time savings that differed substantially from previously established values using the same approach, for reasons that are not clear.

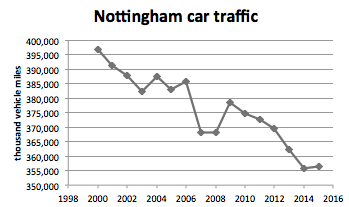

Altogether, the SP approach seems decidedly problematic in establishing sound values for travel time savings. But there is a bigger problem, in that the National Travel Survey shows that average travel time has hardly changed over the past 40 years that this has been measured, despite huge investment in infrastructure justified by supposed time savings benefits. The explanation for this apparent paradox is that the SP experiments use short term trade-offs whereas the NTS recognises the long term outcomes, whereby people take the benefit of investment by travelling further at higher speeds to gain additional access.

Land use change

This additional distance travelled gives rise to changes in land use, as for instance in London’s Docklands, which have been made accessible by public investment in the rail system, permitting private investment in high value accommodation. The economic case for Crossrail, due to open in 2018, was based largely on time savings (user benefits), divided three ways between business, commuting and leisure travellers. To this was added the economic benefits attributed to ‘wider impacts’ (mainly agglomeration effects) not included in the user benefits. What was not included, however, was the increased real estate values since this would be double counting user benefits. So real observable increases in land and property values are disregarded in the standard approach to appraisal, which prefers notional time savings and notional ‘wider impacts’.

Another rail investment appraisal is that for HS2, which is also based mainly on user benefits. The problem in this case is the lack of any indication as to where, regionally, the benefits arise, a serious deficiency given that the intention of the new rail route is to boost the economies of the cities of the Midlands and the North.

Who benefits?

For road investment, the problem with the standard approach based on time savings is the failure to consider distribution of benefits across classes of road users. Congestion arises on the Strategic Road Network in or adjacent to populated parts of the country, where it is used by local users, particularly for commuting, as well as by long distance users. My own analysis suggests that it is local users who get the bulk of the benefit from investment to increase the capacity of the SRN, faster travel permitting more choice of jobs and homes, the extra traffic returning congestion to what it was, with long distance users no better off. If this is right, there is a question of the value of national investment in the SRN that fosters local car-based commuting. The failure to distinguish how the benefits of investment affect different classes of road user means that this question is not addressed. (In contrast, the distribution of benefits to different classes of rail users is possible, because we have data from ticket sales that allow this classes to be distinguished.)

In summary, the travel time savings methodology is problematic because:

- SP values of time are sensitive to context.

- There is only a very tenuous connection between short run SP values and the value of long run real estate development.

- There is no indication of how benefits of investment are distributed regionally (for long distance rail) or by classes of users (for roads).

- Observable changes in land and property values are disregarded, which means there is a disconnect between the economic case for an investment and the business case.

Reliability

A further benefit of transport investment can be improved reliability – improved traffic flow on roads, reduced lateness on public transport. The SP research investigated this and concluded that the ‘Reliability Ratio’ should be reduced from 0.8 to 0.4. (The RR is the value of travel time variability (SD) divided by the value of travel time savings: it enables changes in variability of journey time to be expressed in monetary terms.) This downgrading of the importance of reliability seems at odds with a previous study by DfT that surveyed road users about their preferences. One question asked about priorities if additional money were available: improving traffic flow ranked well above reducing journey times. While not a formal SP investigation, the survey findings suggest that reliability should be the main economic benefit from a user perspective, rather than time savings, which is the reverse of the WebTAG treatment.

Having appropriate monetary values for reliability is important for appraising investments focused on this aspect, for instance variable speed controls for managed motorways and predictive journey time information that mitigates the main detriment of traffic congestion. Such digital technologies are likely to be far more cost-effective that civil engineering technologies in improving the user experience.

WebTAG deficiencies

The DfT’s approach to transport investment appraisal, known as WebTAG (web-based transport analysis guidance):

- Under-estimates benefits of urban rail investments, because the enhancement of real estate values is disregarded.

- Over-estimates benefits of inter-urban road investments, which foster local car commuting.

- Under-estimates benefits of digital technologies.

The Treasury provides central guidance on analytical methods used across government departments. The original Green Book advises on investment appraisal, where the WebTAG approach to cost-benefit analysis is seen as an example of good practice. It is, however, an outlier in the amount of detailed analysis required to be compliant, and hence in the effort required. Other departments are less demanding. For instance, there have been major programmes of school and hospital building in recent years, but there is no theory of how replacing an obsolescent building improves educational or health outcomes, which limits analysis to considerations of cost-effectiveness.

The most recent Treasury guidance is the Aqua Book, which deals with quality assurance in analytical models, and was prompted by DfT’s analytical shortcoming in connection with retendering the West Coast Main Line rail franchise in 2012. One requirement is that analysis should be ‘grounded’ in reality: connections must be made between the analysis and its real consequences. The WebTAG approach fails this test, for the reasons outlined above.

I am not alone in my criticism of the established approach to transport appraisal. The Transport Planning Society conducts an annual survey of its members: ‘Most TPS members consistently say that appraisal methods should be reformed. In the most recent survey, only 3.5% considered current methods did not need reform, with 60% having major issues with them. The top reason for this by some way was the need to appraise changes in land values, land-use or travel behaviour.’

Space not time

Recalling first principles:

- Transport moves people and good through space (not time).

- Investment that increases speed or capacity leads to more movement through space (not time).

- We therefore need an economic framework that recognises spatial characteristics – Spatial Economics.

Spatial economics is a long-established sub-discipline of economics, going back almost two centuries to the seminal work of von Thunen who related the value of agricultural land, as measured by the rents that farmers could afford to pay to landowners, to the nature of the produce grown and the costs of transporting it to the market in the nearest city. This approach was subsequently extended to cities (urban economics) where the cost of housing falls as the costs of travel to employment in the city centre increase. The Spatial Economics Research Centre at the LSE is one source of expertise, although it appears not to have engaged in consideration of the kind of spatial economic analysis that would assist transport investment appraisal by mitigating the deficiences of the time savings approach.